IN THE HOT SUMMER before the cold winter in which our nation entered the second world war to end all wars, two boys were born two weeks apart; one in Illinois and the other in Mississippi.They would never meet but both were murdered at different times in their lives, in and near the cotton-ginning town of Drew in Sunflower County, the heart of the Mississippi Delta. Each would have his place in this country’s civil rights movement.

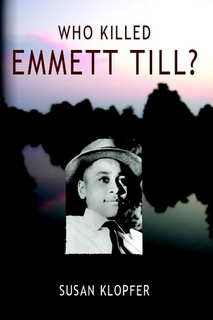

Fourteen-year-old Emmett Till of Chicago, Illinois was kidnapped in the early morning hours of August 28 in 1955 while visiting Mississippi relatives in a small cotton hamlet known as Money, a tiny community spread out on a patch of dirt under very old oak trees with several homes, a few businesses and a red brick church house with a humble graveyard near it.

Accused of whistling at a white store owner’s wife, Emmett Till was kidnapped and taken to a plantation owner’s tool shed at the edge of nearby Drew where he was tortured and possibly killed. His body was hauled by truck to the edges of another small town, Glendora, anchored with barbed wire to a 75-pound metal, cotton gin fan and thrown into the Tallahatchie River.

The sight of Till’s brutalized body in an open pine box casket was shown to thousands of mourners in Chicago a week later, after being returned home from the Delta. And this display pushed many who had been content to stay on the civil rights sidelines directly into the fight. Young Emmett Till’s body showed the world the racial problems belonging to the United States, and gave a new voice for victims of racial injustice.

Among those moved to action was civil rights activist Rosa Parks whose action came twelve weeks after an all-white Mississippi jury, after sixty-seven minutes of deliberation, acquitted J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant of the murder of Till.

Yet some 42 years later, Cleveland McDowell of Drew, a life-long Mississippi attorney and a minister, whose career was unquestionably defined by Till’s brutal murder, was shot to death in his home. As a foot soldier in the modern civil rights movement, his role undoubtedly sparked by the death of Till, McDowell would become a friend to hosts of civil rights leaders including Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. , Rev. Jesse Jackson, Fannie Lou Hamer and Medgar Evers.

In 1963, McDowell became the first black student admitted to the University of Mississippi law school, following in the footsteps of his mentor, James Meredith. All of his professional life, McDowell secretly tracked details of race-based murders, including Till’s lynching, while keeping in touch with Emmett’s mother in Chicago. McDowell was only fifty-six years old when he was gunned down. To this day, most of Mississippi’s civil rights historians seem to forget him. Should his story be told in school books? Afterall, he was whispered to be gay.

Who really killed Emmett Till? The “answer” appears to have been documented but were only two men involved? What did Cleve McDowell know about this murder? What happened to his boxes of papers and evidence of the murders of Till and countless other African Americans in Mississippi? Was McDowell working on other key murders? Who killed McDowell? What could he have known? Who wanted him dead?

Review:

By Max G. Bernard

This is a well-written and fascinating book about a vicious lynching of an African-American teenager from Chicago while visiting Mississippi. His mother insisted on an open coffin for the services so that people could see what was done to her son. The author explains the history, demands justice, talks with some of those still alive who, as she says, “still had the story fresh in their hearts and minds.” After you read this book, the events will live in your heart and mind too, because she makes it come alive. This is highly recommended.

.